Cereal crops like rice and wheat feed much of the world, providing up to 80% of daily calories in some regions, yet cereals are often low in essential nutrients. CSU researcher Davina Rhodes, assistant professor in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, is trying to change that. With a $638,000 grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Rhodes is investigating genetic approaches to improving the nutritional quality of sorghum, a staple cereal crop for millions of people around the world. In parts of the world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and southeast Asia, where there are high rates of malnutrition, sorghum is often cooked as porridge or ground into flour and used to make flatbread. It has also been gaining popularity in the U.S. with the rise in demand for gluten-free and “ancient grain” products.

Fighting vitamin A deficiency

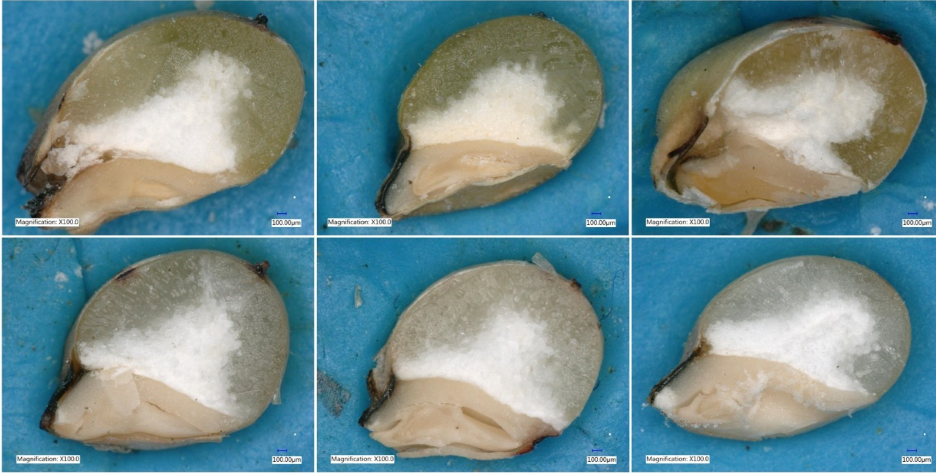

Rhodes and her collaborators from University of North Carolina and Arkansas Children’s Nutrition Center are trying to identify sorghum varieties that have high concentrations and bioavailability of grain carotenoids, which are compounds that turn into vitamin A in the body.

“The bioavailability of a nutrient refers to how much of the consumed nutrient actually gets absorbed into our bodies,” said Rhodes. “Our bodies are not 100% efficient at utilizing the nutrients we consume, and some crop varieties have nutrients that are more bioavailable than in other varieties. So, we want to find sorghum varieties with high levels of bioavailable carotenoids, which, when eaten, would help people get the vitamin A they need.”

Vitamin A deficiency is a major problem globally, particularly for young children and people who are pregnant and breastfeeding. It leads to severely decreased immune function, making common illnesses more fatal, and is also the leading cause of preventable blindness in young children.

“Biofortification of staple crops can be a tool in fighting malnutrition, particularly in the most vulnerable regions of the world where subsistence farmers rely on the food they grow themselves to feed their families,” said Rhodes.

The ‘camel of crops’ – growing sorghum in a changing climate

Biofortified sorghum could serve to open new high-value markets for farmers and food processors. Sorghum is also more climate resilient than many other crops, Rhodes says, and may become more important for both human food and animal feed as the world increasingly feels the effects of climate change.

“We need to transition to crops that can withstand the increased environmental stress. Sorghum is the ‘camel of crops.’ It’s one of the few crops that can be grown in very dry and hot environments, which is why it is so important in sub-Saharan Africa. With climate change, sorghum will become an increasingly important crop for global food security.”

Using a genetic approach

The research team will use tools from crop genetics, analytical chemistry and human genetics to identify which genes are responsible for high versus low carotenoid concentrations and bioavailability. This knowledge can then inform breeding efforts to grow nutritionally improved sorghum.

Fortifying cereal crops for vitamin A is not a novel idea – in the 1980s there was excitement and controversy around Golden Rice, a genetically-engineered grain that was developed with the same goal of reducing global vitamin A deficiency.

“Rice does not have the necessary genes to produce carotenoids in the rice grain, so the only option available to the scientists working on Golden Rice was to introduce genes from another species, making it a genetically modified organism,” said Rhodes. “GMOs are immensely controversial in the general public – although research overwhelmingly shows that there are no health concerns related to consuming GMO foods. But at this point in time, a non-GMO biofortified crop will be the most acceptable to consumers.”

Fortunately, sorghum does have the necessary genes to produce carotenoids in the grain, which will enable Rhodes to develop non-GMO genetic approaches, combined with traditional breeding, to develop a high carotenoid sorghum.

Preventing nutrition-related disorders

Rhodes started her career as a registered dietitian, working primarily with patients with diabetes in a medically underserved community in Chicago.

“The people I saw in the hospital were so sick by the time I would see them, that at times I felt hopeless about improving their quality of life. Through that experience I came to realize that I needed to work on solutions to prevent rather than treat nutrition related disorders.”

With expertise in both human nutrition and crop genetics, Rhodes has a unique perspective on crop improvement as it relates to health and disease and plans to use that perspective to help end global malnutrition.