Each year, the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (NSF-GRFP) awards 2,000 master’s and Ph.D. students with five years of financial support in their research endeavors.

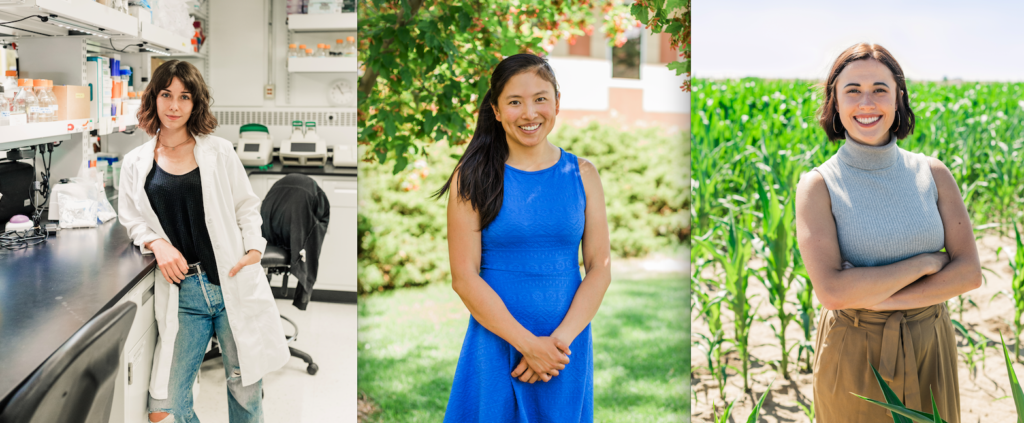

In 2020, three of those awards were granted to students in the College of Agricultural Sciences’ Department of Agricultural Biology. Grace Johnston, Lily Durkee, and Kirsten Hein are remarkable students who received this distinguished award, and their research stretches the gamut of agricultural implications.

We sat down with the awardees and their advisers to hear about the research they will be conducting after receiving the NSF award.

Lily Durkee, graduate student

In the field of evolutionary ecology, Durkee combines the ideas of evolution with ecological processes.

In the field of evolutionary ecology, Durkee combines the ideas of evolution with ecological processes.

“One way to picture these ideas is to look at the response of a population to an environmental stress event,” Durkee said. “When a population is degraded, it can become really small, or it can be fragmented into a bunch of pieces—the animals or plants living there have to either adapt to the new environment, or they’ll go extinct.”

If you think about a population getting really small after a big pollution event, for example, only a handful of the individuals can survive. This small population can then be supplemented by a non-polluted “source population” of good-quality habitat. These healthy individuals coming into the population will increase the population size and also boost genetic diversity. This helps the small population have a better chance of recovery through the process of adaptation.

When a population shrinks and then can grow again because of adaptation, this is called “evolutionary rescue” because evolution is happening quickly enough to rescue the population from extinction.

This research is relevant not only today but also for the future. As humans continue to negatively impact the environment, animals and plants must be able to adapt to their ever-changing surroundings. Durkee’s research specifically looks at the impacts of dispersal or the movement of individuals from one habitat to another. Her research asks the following question: How does dispersal influence the probability of a population recovering after an environmental stress event?

“My lab uses a small beetle called the red flour beetle in experiments, which are historic pests of grains worldwide,” said Durkee. “They’re a terrible pest, but they’ve also been cultivated as a model organism for use in ecological and evolutionary laboratory experiments. They live in small boxes of flour, and I can put a set number of beetles in each box and to represent an animal population. I’m going to be adding a pesticide to the flour to model environmental stress. This will kill most of the individuals but not all, and then I will see if dispersal can optimize population recovery. Using a model system in this way is neat because I can model animal populations in the lab without causing any harm to natural populations.”

Having a student win this award “is definitely not business as usual, these are really challenging to get, and really prestigious,” said Ruth Hufbauer, adviser and professor of applied evolutionary ecology. “I had one when I was a graduate student and it made all the difference because it pays better than typical graduate student salary, allows you to branch out in your research and opens so many doors.”

Reviewers and NSF program managers look at the ideas presented and the student’s record. “The idea is to support and grow the American scientific workforce through supporting outstanding graduate students,” Hufbauer said.

“It’s a real testament to how outstanding our students are in Agricultural Biology,” said Hufbauer, “and also to how well students and their advisers are working together. It has to be the student’s work but in collaboration with an adviser who has experience grant writing. That our students are so outstanding, and our students and advisers work well together speaks well of our department.”

Hufbauer is excited about two things Durkee brings to the table: writing and math.

“She’s a really good writer,” said Hufbauer. “She has written two novels. That is a skill that lots of scientists come to after the fact when they realize, ‘Oh my gosh, I have to communicate what I’m doing, not just do it!’ It’s not meaningful if you can’t tell people about it. Lily already has that skill.”

Kirsten Hein, Ph.D. student

For the NSF-GRFP, Kirsten Hein proposed to study the molecular mechanisms that interact with variable abiotic environments to create complex root traits in a biparental population of recombinant inbred maize (corn) lines. If that sounds in-depth, that’s because it is.

For the NSF-GRFP, Kirsten Hein proposed to study the molecular mechanisms that interact with variable abiotic environments to create complex root traits in a biparental population of recombinant inbred maize (corn) lines. If that sounds in-depth, that’s because it is.

“Climatic stress is an important and ubiquitous selective agent in plant evolution and a major limiting factor to crop productivity,” Hein said. “Root traits are major targets for the second green revolution because of their potential to improve crop productivity, increase drought tolerance, and increase capture of carbon in the soil.”

To better understand the traits that drive performance in agricultural systems, Hein merits it is important to consider how they are affected by genotype, the environment, and the interactions between the two.

Regarding the broader implications of her overall research, Hein said, “The impact of climate change on drought frequency will impose a significant economic cost in the U.S., especially in the southwest and Rocky Mountain states. It is imperative to develop drought-resilient maize cultivars without comprising agricultural yields. Enhanced root systems with deeper architecture are predicted to improve seasonal water-use efficiency, predominantly under drought conditions. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that control these complex root traits and incorporating them into modern agriculture could potentially mitigate the social and economic risks of systemic crop failure.”

Hein believes her academic record, four years of interdisciplinary research, and passion for mentoring undergraduate students in STEM demonstrated her commitment to learning and aligned with the NSF’s mission.

“I contribute a major component of my success with the NSF Award to the encouragement and support I received from my colleagues, peers, family members, and adviser, John McKay, throughout the application process,” said Hein. “As a graduate student, my short-term goals are to continue mentoring undergraduate students and to increase their exposure to research opportunities in STEM. For my long-term goals, at the moment, I aspire to have a career with the USDA-Agricultural Research Service to continue broadening our nation’s scientific knowledge on sustainable agricultural systems and understanding of the molecular drivers that influence these systems.”

Hein’s adviser, McKay, studies the process of how organisms adapt to different selective pressures. In particular, how different populations adapt to the local climate that they’re in.

“If you think about Ponderosa pines, growing in this part of Colorado versus wet places in British Columbia, well, what changes take place at the organismal and genetic level to allow them to do well in each particular place?” McKay started. “We don’t study pine trees because they live too long. We only study things that live a year or less because that gives us a much better chance of learning something in our lifetime.”

McKay’s lab works with brassica, canola, rice, sorghum, and maize.

“Right now, almost all the work we’re doing is in corn, or maize, as we call it. We’re finding drought-related traits and the genes controlling them in maize, which in turn, can be used in breeding programs to create hybrid varieties for production in the US and other places.”

McKay is savvy about the impacts he has whilst training graduate students. At any given time, he typically mentors two graduate students and two Ph.D. students.

“Kirsten has undergraduate training in genetics, statistical analysis and computation. She also has training in evolutionary biology and has research experience, ranging from disease breeding in trees to more organismal and molecular biology approaches.

My job is to create independent scientists, and any way that they can create independent projects and get funding – that’s getting us towards that goal.”

Grace Johnston, graduate student

Johnston’s work focuses on elucidating plant hormonal crosstalk concerning growth and defense against pathogens using the model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana, commonly known as thale cress. Currently, she is working on the characterization of a triple-knockout mutant that is involved in the interaction between two important plant hormones.

Johnston’s work focuses on elucidating plant hormonal crosstalk concerning growth and defense against pathogens using the model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana, commonly known as thale cress. Currently, she is working on the characterization of a triple-knockout mutant that is involved in the interaction between two important plant hormones.

“Even though I am in the beginning stages of my scientific career, I hope this research will greatly impact the larger agricultural community,” Johnston said. “By furthering investigations of the complex network of interactions regulating the balance between plant growth and immunity, future efforts in synthetic biology can be used to develop advanced crops with increased pathogen resistance and superior plant yield.”

With climate change and the global population steadily climbing, Johnston understands that feeding the human population utilizing current agricultural practices will likely be problematic at best. “As the plant growth defense trade-off could be a key factor in combating this, my research project aims to help solve this food shortage problem for future generations.”

When asked about what it means to be a recipient of such an esteemed award, Johnston said, ”It is a huge honor to be awarded the NSF GRFP. With this award, my research will be funded throughout my graduate career, allowing me to focus solely on science. This is an incredible privilege, as many graduate students struggle with balancing teaching, taking classes, and conducting research simultaneously. As the saying goes, it takes a village. Without the steady support of my family, friends, lab-mates, the encouraging mentorship of Cris Argueso, and the invaluable opportunity to work in the lab throughout my undergraduate career, I could not have accomplished this achievement.”

Argueso knows that great scientists start with great students.

“You have to start with a student that is dedicated, that has shown commitment not only to their studies but to research.”

The NSF fellowship application has two parts. First, the research, which they call intellectual merit. Second, broader impacts. In a nutshell, the broader impacts are how the student is going to justify their funding.

“Broader impacts help verify the research and become part of society or benefit society,” said Argueso. “I have excellent students in my lab, and they’re very interested in broader impacts and making sure their research has a tangible benefit to society. Either by becoming something to help agriculture directly or by mentoring. That part is very important for the NSF application.”

Grace is “going to create these programs together with a Fort Collins high school and CSU,” said Argueso. “The students are going to go into the conservatory in our Plant Growth Facilities, where they will study plant architecture. So, they will look at how plants are formed, what are the angles a plant makes, how is one plant different than the other – learning all about plant form. What she’s proposing to study is that there is some mathematical modeling that you can do off plant form to understand the genetic components for plant growth.”

Essentially, the visiting high school students will photograph different plants, and Johnston will teach the students how to extract mathematical data from the plant shape and form.

The third part of Johnston’s broader impact is a collaboration struck with the Art Lab in Fort Collins. Pictures taken by students will be featured in an art exhibit once the project is complete. The same photos students utilize to learn plant form are going to be made into a massive collage.

Johnston is now educating high-school students and the general population about how plants grow, how mathematics is involved, and outreach through art.

“The other thing about [Johnston] is she’s a great photographer,” said Argueso. “I think that’s a great example of how someone can not only do science but also integrate that science to society. That is an essential part of her project. And I think, you know, a very important reason why she got this fellowship. Her success is first and foremost the results of her efforts, and I am very lucky to have her in my lab.”