There’s an empty grain sack emblazoned with a logo from a Senegalese farm cooperative tacked to the wall in Geoff Morris’ Colorado State University office. Morris, an associate professor of crop quantitative genomics in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, hung the fabric bag in eyesight as a way to keep in mind the practical impact of his research. “I have this to remind me what I’m doing every day,” Morris said.

What Morris is doing is using his training as an evolutionary geneticist to practice what he likes to call personalized medicine for plants — using advanced breeding techniques to find and enhance optimal traits to make a crop more resilient and productive. “We can go into the genome, figure out why a problem is happening and then we can swap out the genes using breeding,” he said.

Running a lab for the past 10 years, Morris has worked on all kinds of plant breeding projects. There is one in particular, though, that has captured most of his attention: helping West African farmers improve sorghum, a staple cereal grain grown in the grasslands south of the Sahara Desert. “We’re doing this personalized medicine for crops that are grown by people who make $1 a day,” Morris said. “The farmer groups and plant breeders co-design the crop technology with us and then implement the technology.”

Now, thanks to a five-year, $10 million grant from the Gates Foundation, Morris is expanding his so-called Green Evolution sorghum project to other parts of Africa and incorporating work on another climate-smart grain, pearl millet. Morris’ proposal was shepherded through the Foundation’s rigorous grant process by Jeffrey Ehlers, a senior program officer who works on agricultural development projects. Ehlers said the Gates Foundation decided to fund Morris’ work because it has significant potential to impact a part of the world that desperately needs it.

“That area of Africa has some of the highest birthrates and some of the most food insecure populations anywhere in the world. These crops help those populations directly.” Ehlers said. “We felt they needed a boost on the upstream end. Geoff has shown he can help do that, and he has the experience working in West Africa.”

On the ground

Morris’ introduction to the world of plant breeding arrived more than a decade ago, when he was hired for his expertise in genome biology to characterize certain genomic patterns in sorghum. He published that work in 2013. Near the end of the paper, Morris noted that plant breeders could use this new information to breed more climate resilient crops.

During the publication process, however, Morris received a comment from someone who questioned whether breeders would actually do what he’d proposed. “One of the reviewers said, ‘I don’t think this could really be used to breed for climate resiliency,” Morris said. “I thought, gosh, yeah, I guess I should actually make that happen.”

From there, the Morris lab was born. To get started, he landed an initial, modest grant, and traveled to Senegal to better understand the challenges growers faced. Morris looked for traits that would improve their sorghum crops; he also started to develop the technology necessary to breed varieties that are more resistant to drought and disease and, in collaboration with a nutritionist, more nutrient rich.

Since the beginning of the project, Morris said, it’s been important not to ask farmers to make significant changes to what they do and instead work with crops they prefer and are already planting. “We try to take traditional varieties and help them make it even better,” Morris said. “For example, we took a variety that’s already really good, but is susceptible to drought and we bred in a gene to make it more drought tolerant, and also to make it resistant to this parasitic weed.”

One of Morris’ early collaborators was a student he met in Senegal, Jacques Faye. Growing up in a small farming village, Faye developed a passion for agriculture early on; his parents were both farmers and he recalls planting mango and lemon trees as a young boy.

In high school and college, Faye studied biology and crop adaptation, and eventually worked his way to completing a doctoral degree under Morris. “Part of my mission is to cultivate food security in sub-Saharan Africa,” Faye said. “And I believe a major aspect of food security is improving crops that can adapt to any kind of environmental variation because our region is very vulnerable to climate change.”

Faye now works for a research institute in Senegal and is an on-the-ground partner with the Morris lab alongside CSU team members such as Alex Kena and Safietou Fall. (Kena is a postdoc researcher and Fall is pursuing her doctoral degree.) In all, Morris has a team of 30 people working on the Gates-funded project.

Both Kena and Fall were attracted to the work because it presented an opportunity to have a positive impact with local farmers. “Beyond academic papers, Geoff’s program is designed to have real benefits to society, affecting policy and the well-being of people,” said Kena, who grew up farming in West Africa with his grandmother. “These are the things that make me passionate about this program.”

The Colorado Connection

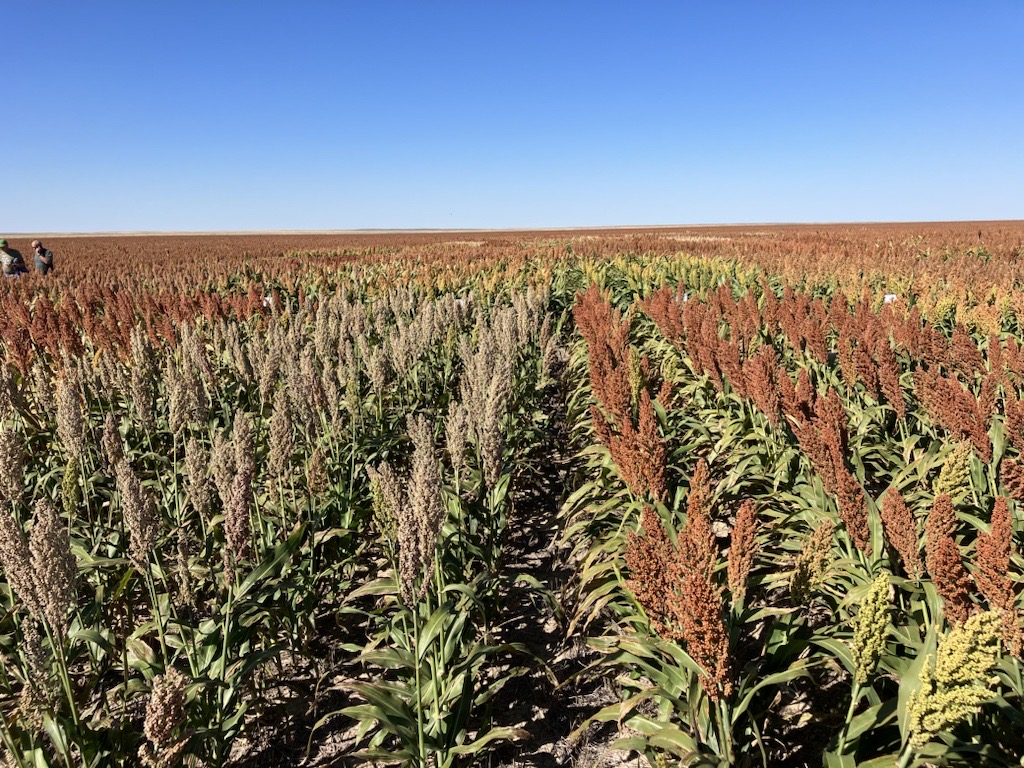

Early on, Morris recognized another opportunity for sorghum breeding, something much closer to home. Right now, U.S. farmers plant about 10 million acres of grain sorghum, also known as milo, and forage sorghum, including across the southeastern corner of Colorado. “Southeast Colorado has a lot in common with sub-Saharan Africa despite the fact that they are very different places,” Morris said.

Given the hot and dry climate in this part of the state, he said, sorghum can be a better option than, say, corn, which requires significantly more water. (Southeast Colorado farmers are lucky to receive 14 inches of rainfall annually compared with parts of the Midwest that regularly receive more than double that amount.)

“Corn takes a lot of moisture,” said Jay Haase, a southeast Colorado farmer who has planted sorghum grain for years. “Milo is much more consistent with lower rainfalls; with our shorter season, it just works better for us.”

Haase uses sorghum as a kind of rotational cover crop. He sells the grain for all kinds of uses — animal feed for dogs, cats, chickens, hogs and birds as well as food-grade varieties used to make milled flour, pastries or chips. It’s also gluten-free and can be used to make a molasses-like syrup. “It’s amazing what milo can be used for,” Haase said.

There are still challenges, though. Right now, Haase plants sorghum late in the season, around mid-May. Given that sorghum thrives in a hot and dry climate, if he plants it too much earlier the seeds can get damaged in the cold. Problem is, the crop can still be negatively impacted by drought later in the summer.

Morris viewed all this and saw opportunity: If Great Plains farmers like Haase could plant sorghum a little earlier, there’d be enough moisture in the ground to keep the grain happy through the summer. He began working on a project to breed sorghum varieties that are more cold tolerant, which would allow farmers to get the seed into the ground earlier in the season.

Eugene Kelly, director of CSU’s Agriculture Experiment Station, said sorghum has a high potential to add resiliency to the state’s agriculture system. “It’s gaining lots of interest with producers in Colorado because of its heat and drought tolerance” Kelly said. “There are also increasing opportunities to develop markets for flour, feed for livestock and even gluten-free products.”

All of this has Haase excited about the future of sorghum in his corner of Colorado. “For us, corn just doesn’t make sense; it’s very expensive and inconsistent because of our rainfall,” Haase said. “I think the sky’s the limit on milo. It’s improving all the time.”