Researchers are looking belowground to address atmospheric carbon, using soils as a tool for climate mitigation. Accessing roots and soils has historically required some creative problem-solving to take a deeper look at the rhizosphere, or the soil around a root system.

“Studying carbon and nitrogen transformations at the rhizosphere level is very hard,” said Francesca Cotrufo, professor in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences.

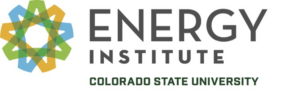

To address this challenge, the Energy Institute’s Rapid Prototyping Lab worked with Soil Carbon Solutions Center scientists, including Cotrufo, to design and manufacture Colorado State University’s first rhizotron prototype with plans to make several more. A rhizotron allows scientists visibility and access to the roots and soil surrounding them at each depth along their extension through the soil profile.

These engineers and ecologists are working together to build solutions to carbon by reducing atmospheric greenhouse gases: methane and carbon dioxide. Natural carbon reservoirs include oceans, sediments, vegetation and soils. Regenerative agricultural practices can draw down atmospheric carbon to soil reservoirs, reducing agricultural net greenhouse gas emissions. The new rhizotron will be used in studies to inform regenerative agriculture research.

The new rhizotron

“The state of the research for soil carbon and plant-microbial interactions is currently limited by our ability to study in vivo root dynamics and their impact on the soil biota and the biogeochemical processes controlling carbon, nitrogen and water exchanges between plant, soil and the atmosphere,” said Cotrufo.

With capacity to view living roots and access them for sampling, rhizotrons are useful for soil scientists developing climate mitigation techniques. For example, scientists can track carbon isotopes taken into a plant during photosynthesis as they distribute to roots, root symbionts and the mineral soil to determine where the most carbon ends up under specific experimental conditions. Understanding gleaned from such carbon studies can inform agricultural management practices for soil regeneration and carbon sequestration.

John Mizia, research associate at the Energy Institute and director of the Rapid Prototyping Lab, said that no other rhizotrons his team explored functioned like this new design. This new rhizotron is unique, in part, because of the environmental controls and capacity for building customized units.

“Basically, this rhizotron will have windows along the soil profile to access the roots and the soil when the plant is alive,” said Cotrufo. “Being modular, you could design it to experiment with replicates.”

The capacity to build out these modular units into a customized set up that fits the experimental design needs of a given project broadens opportunities to conduct new experiments that answer questions about roots and the soils surrounding them.

The Rapid Prototyping Lab is an applied engineering and advanced manufacturing facility with computer numerical control (CNC) machinery, 3D printing, welding and other tools and materials available to support researchers across the university. The team was excited to work on this interdisciplinary project.

“I programmed and water jetted a good portion of the aluminum parts needed to hold the polycarbonate windows onto the Rhizotron unit along with finishing the surface in preparation for final assembly,” said Alex Willman, student lab technician in the Rapid Prototyping Lab.

Future soil carbon research

Cotrufo studies the formation and persistence of soil organic matter alongside global environmental changes and disturbances. Her research also focuses on applying these understandings to inform soil management practices that mitigate climate change. Erica Patterson is a student in Cotrufo’s Soil Innovation Laboratory pursuing a doctorate in the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology. Patterson will be the first to test the Rhizotron.

“Erica Patterson just received a research fellowship from the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology to test how simulated grazing affects the amount of carbon that those roots put in the soil,” said Cotrufo. “She has designed it to do without the rhizotron but will be testing the rhizotron along the way so that further studies can be done with that unit in the future.”