Irrigation pumping on U.S. farmland accounts for approximately 16% of all greenhouse gas emissions from energy use in agriculture, forestry and fisheries, according to new work led by Colorado State University researchers published in the journal Nature Communications.

“Irrigation is a super promising adaptation strategy for climate change,” said Avery Driscoll, a doctoral student in CSU’s Department of Soil and Crop Sciences and the paper’s lead author. “But we knew very little about irrigation’s impact on greenhouse gas emissions.”

Driscoll and her co-authors spent two years analyzing multiple data sets to generate irrigation energy emissions estimates for all 50 states. Data included on-farm irrigation pumping information reported in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Irrigation and Water Management Survey, fuel expenditure data and county-level estimates of water demand by crop.

Particularly in agriculture, Driscoll said, most existing emissions estimates have been production-based rather than consumption-based. This shift in thinking has the potential to aid farmers, scientists and policymakers long-term, she said.

“We think it’s valuable to think about this from the end-user perspective,” Driscoll said. “If we know, ‘OK, irrigation is using this much energy,’ then we can target a specific activity to achieve some of our climate goals.”

Beneath the surface

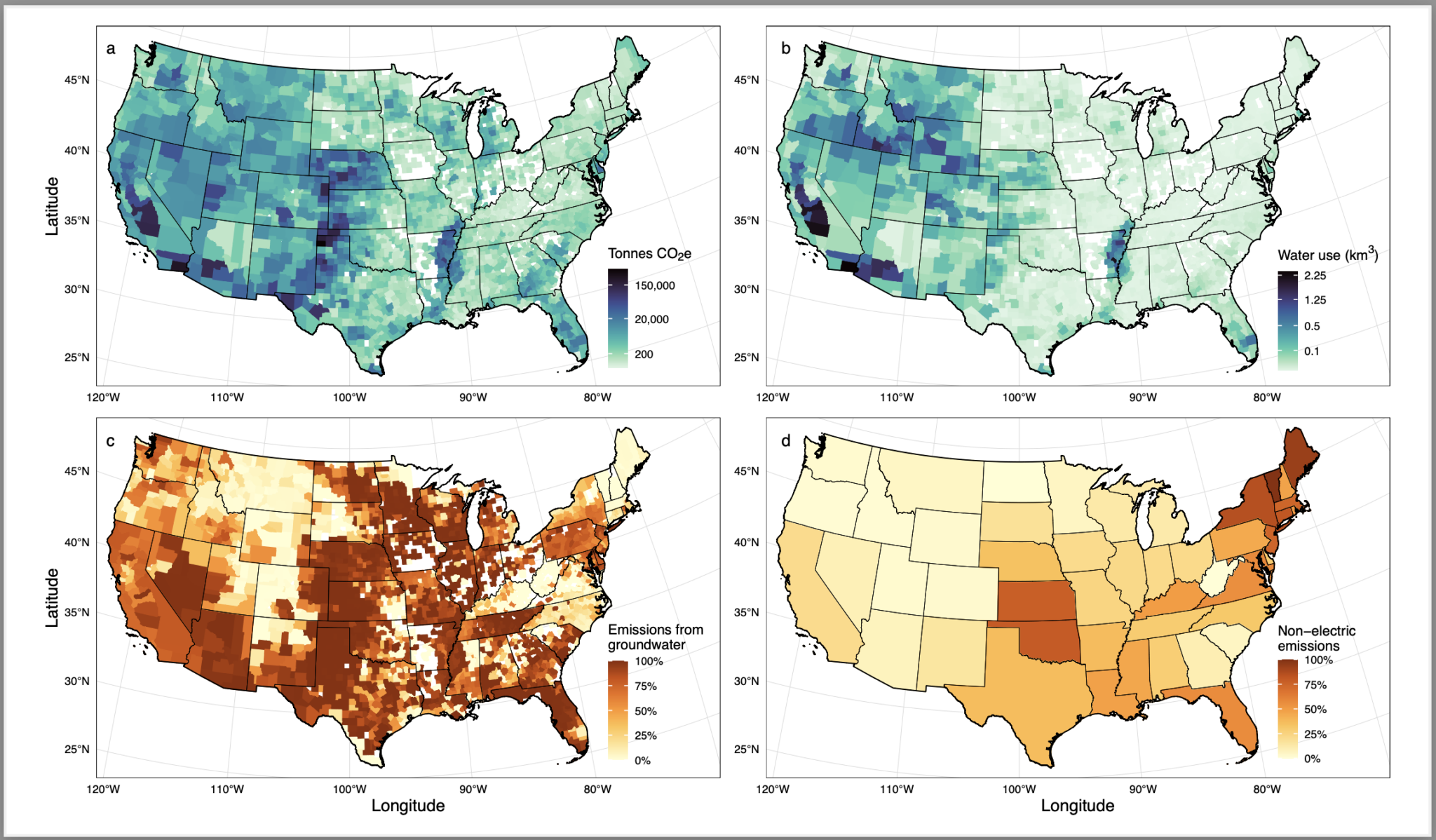

Emissions impact varied greatly depending on several factors, according to the study. Notably, groundwater pumping contributed to 85% of all on-farm irrigation emissions even though groundwater accounted for just under half of irrigation water use across the country. The rate of emissions for groundwater irrigation use was five times greater than for surface water, according to the study.

What’s more, the depth of the groundwater being withdrawn had a significant impact. The study’s authors noted that “emissions from groundwater utilization will increase as aquifer levels decline in areas where rates of extraction exceed rates of recharge.”

“Emissions were really heavily dominated by groundwater pumping,” Driscoll said. “So, for thinking about the issue of how we reduce emissions, that’s something to keep in mind.”

Location, location, location

The significance of groundwater pumping also meant that emissions numbers tended to differ significantly based on location.

“Emissions were really spatially heterogeneous,” Driscoll said. “By doing this analysis at the county level we were able to start to pull out some of those patterns.”

Grouped by state, Texas, Nebraska and California produced the highest emissions, accounting for 46% of irrigation-related greenhouse gas emissions even though those states contain roughly 39% of the cropland. States in the Northeast and upper Midwest saw the lowest irrigation emissions totals.

Viewing the data at a more granular level, however, told a slightly different story. The 237 counties that sit atop the High Plains Aquifer “had a particularly outsized contribution to national emissions, accounting for 44.7% of irrigation energy use emissions despite containing only 27.6% of all irrigated area.”

The High Plains Aquifer, also known as the Ogallala Aquifer, spreads 174,000 square miles across eight Midwestern states, and is the main water source for one of the country’s most significant agricultural regions.

On the other hand, the Colorado River Basin, although more arid, relies heavily on surface water; the region produced comparatively lower emissions numbers, accounting for about 9% of national pumping emissions, according to the study.

Electrification matters

The type of fuel used to operate an irrigation pump was another significant factor in the study’s estimates. Electric pumps were the most widely used, accounting for nearly 70% of pumping emissions.

Electric pumps produced lower average emissions than devices powered by natural gas or other types of fuel. They also present a significant opportunity because of the widespread efforts already underway to decarbonize the electrical grid.

“A big takeaway from this study is that electric pumps are key to decarbonizing our irrigation systems,” said CSU Associate Professor Nathan Mueller, a co-author on the study. “As the electricity grid gets cleaner, emissions from electric pumps will decrease. So, if we can transition natural gas, diesel and propane pumps to electric pumps, we can accelerate this decarbonization.”

Crops and what’s next

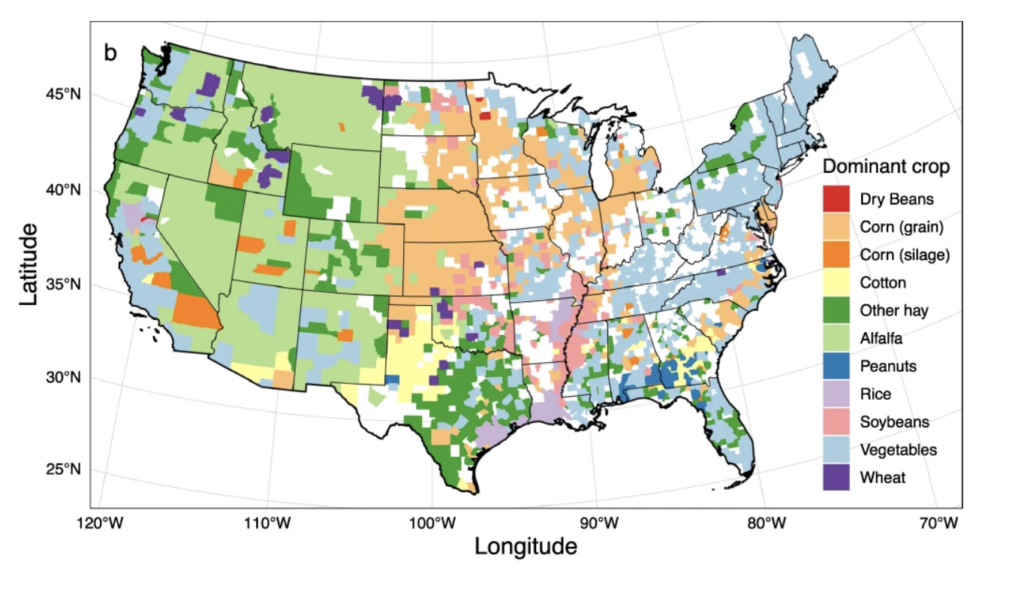

The study also estimated emissions based on 12 major irrigated crops, finding that corn grain “produced the most total emissions by a large margin.” Soybeans were the lowest emitters of the 12 crops analyzed.

Whether it’s crop, fuel type or location, understanding emissions impacts from irrigation can help the agricultural industry better meet the significant challenges posed by climate change, Driscoll said. (Food production accounts for about one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions.)

“Irrigation expansion for climate change adaptation is not going to be random,” Driscoll said. “We’re seeing contractions in the Western U.S., where we have these water scarcity limitations, and are seeing expansion in the Eastern U.S., where we’re seeing more frequent and intense drought, incentivizing the adoption of irrigation because they still have a water supply.”

Although Driscoll said irrigation was a particular blind spot, she hopes new work will continue to examine emissions and energy use at a more detailed level. “This analysis really highlighted to me the value of getting this kind of management-activity level data,” she said. “Then we can make decisions about mitigating our emissions in a way that doesn’t negatively impact our production.”